Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation (1994)

1987-PresentWhat Happened

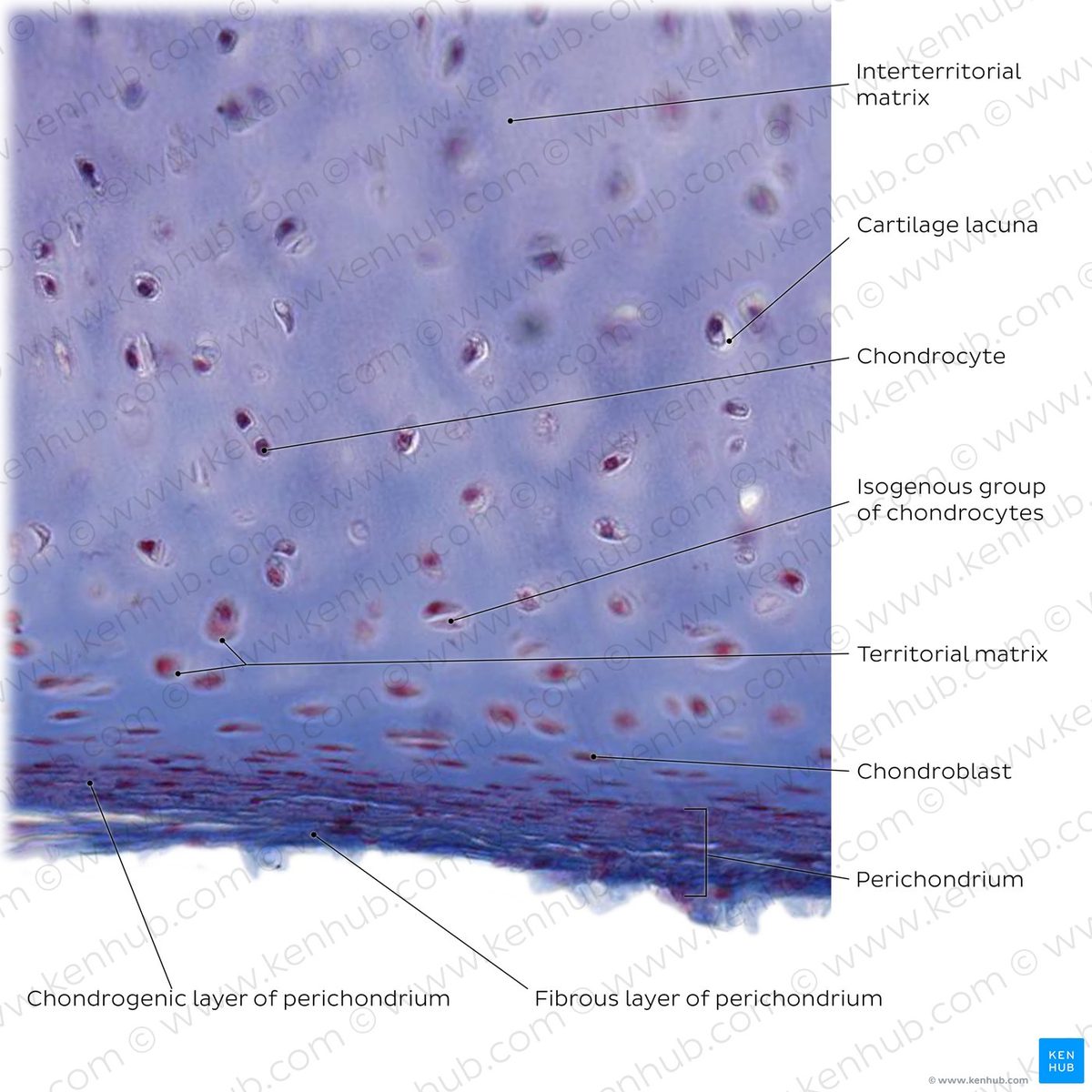

Swedish surgeon Lars Peterson performed the first human autologous chondrocyte implantation in 1994, after proving the concept in rabbits in 1987. The procedure harvests a patient's own cartilage cells, grows them in a lab, and reimplants them into the joint. Carticel became the first FDA-approved cell therapy for cartilage in 1997.

Outcome

ACI established that cartilage regeneration was possible, spawning a new field of cell-based therapies and multiple commercial products.

Despite 30 years of development, ACI and its successors remain limited to focal defects in younger patients. They cannot treat the diffuse cartilage loss of osteoarthritis and require surgery. No cell therapy has become standard of care for age-related cartilage degeneration.

Why It's Relevant Today

The Stanford approach bypasses the core limitation of cell therapies: it doesn't require transplanting cells. Instead, it reactivates the patient's existing chondrocytes, potentially enabling treatment of the diffuse damage characteristic of aging.